Derrick Henry & the (Increasingly Rare) Urban Legend Running Back

Generations will look back at the Ravens back as a legend of the era, but he might be the last of his breed in a sport that is obsessed with analytical efficiency over creativity

When I was kid, my first exposure to football was through my grandmother. We would get on the phone and she would tell me about one player in particular: Detroit Lions running back Barry Sanders. She would tell me how Sanders was this untouchable and shifty ball of energy, making defenders look foolish every Sunday. It was a story of mythology and awe, that has often resonated when talking about the running back position historically.

Today, that reverence has largely disappeared. The running back position has become increasingly specialized, removing the incredible in favor of nuanced efficiency. Player skill sets are exploited in a committee system and are typically discarded faster than any other position. This rule, however, has an exception, and his name is Derrick Henry. At 31 years old, Henry is defying the expectations placed on him and the running back position—showing us why he may be the last of a dying breed at the position.

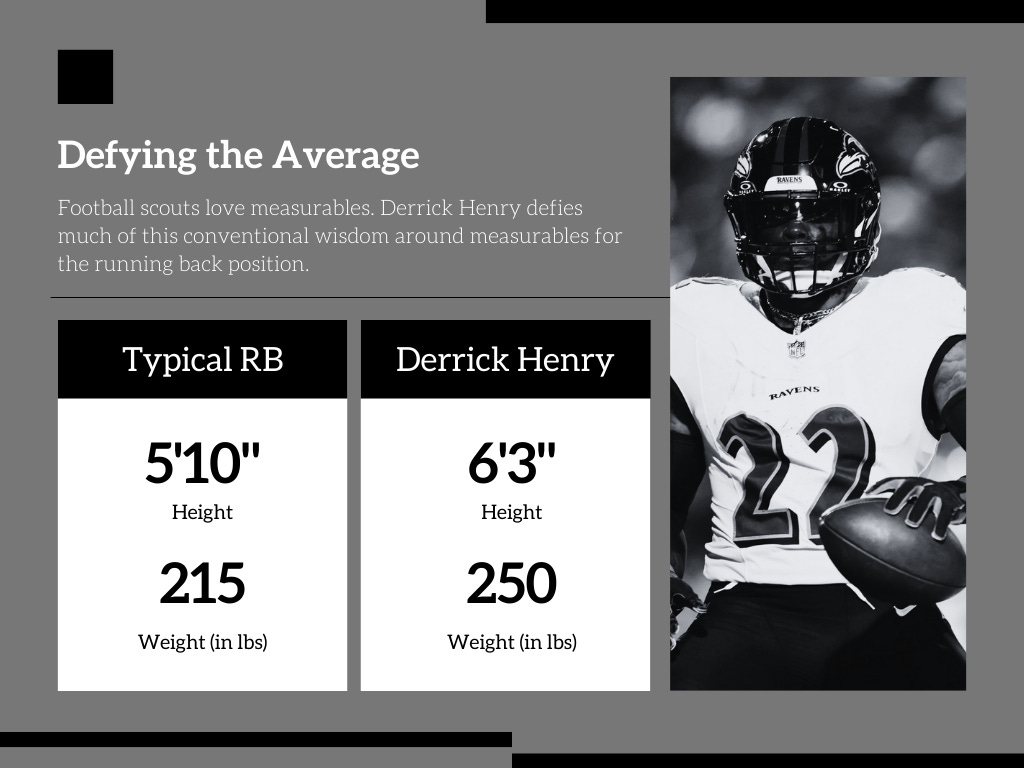

Built Differently

Conventional wisdom for the running back position has long dictated that the ideal size for the position is around 5’10” and 215 lbs. This combination provides a decent mix of power and speed to be effective in the modern game. There have been a few exceptions to this thinking, for instance Hall of Famer Eric Dickerson was 6’3”. But even Dickerson met the weight requirement of 220 lbs. Derrick Henry, measuring in at 6’3” and 250 lbs., defies any sense of conventional wisdom.

Much like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Derrick Henry has dominated at every level he has played. He holds the record for most career rushing yards on the high school level with 12,144. In college, as the feature back for Alabama in 2015, he led the country in attempts, yards, and touchdowns, winning the Heisman Trophy. His 2,219 yards rushing that season is the seventh most in a single season in the history of college football. And as a pro, he is 18th all-time in rushing yards (likely to crack the top ten by the end of this season) and 6th all-time in rushing touchdowns.

The combination of dominance at all three levels of the football timeline create a mythological figure that captures the imagination. Henry does not look like his contemporaries, and he has played like it throughout his football life. He is the type of player where after he retires, his contemporaries will come on to TV shows and podcasts and talk about how prolific and terrifying he was to behold in person. Henry is the latest in a long line of urban legend-like figures that invoked fear and awe in opponents and fans at the running back position.

There have been a few players that fit this sort of physical specimen persona. Earl Campbell in the 70s was a power back that literally ran through defenders with 36-inch thighs that ensured that he almost never went down on initial contact. Barry Sanders in the 90s offered the shiftiness and change of direction that made defenses look foolish as he turned a three yard loss into a spectacular 10 yard gain. And LaDainian Tomlinson helped to redefine versatility in running backs—shouldering the load running the ball while also being a receiving threat, a combination that we hadn’t seen much of until he entered the league.

For Henry, it is the rare combination of breakaway speed and ruthless power that sets him apart. He is a player that finds contact, bounces off, and punishes defenders with the best stiff arm we’ve seen in decades. Last season, 33% of his rushing attempts came against eight or more defenders in the box (the highest rate in the league for running backs with over 200 carries) and it still didn’t matter. Because of his frame and the way he runs the ball, his longevity is the true mystery.

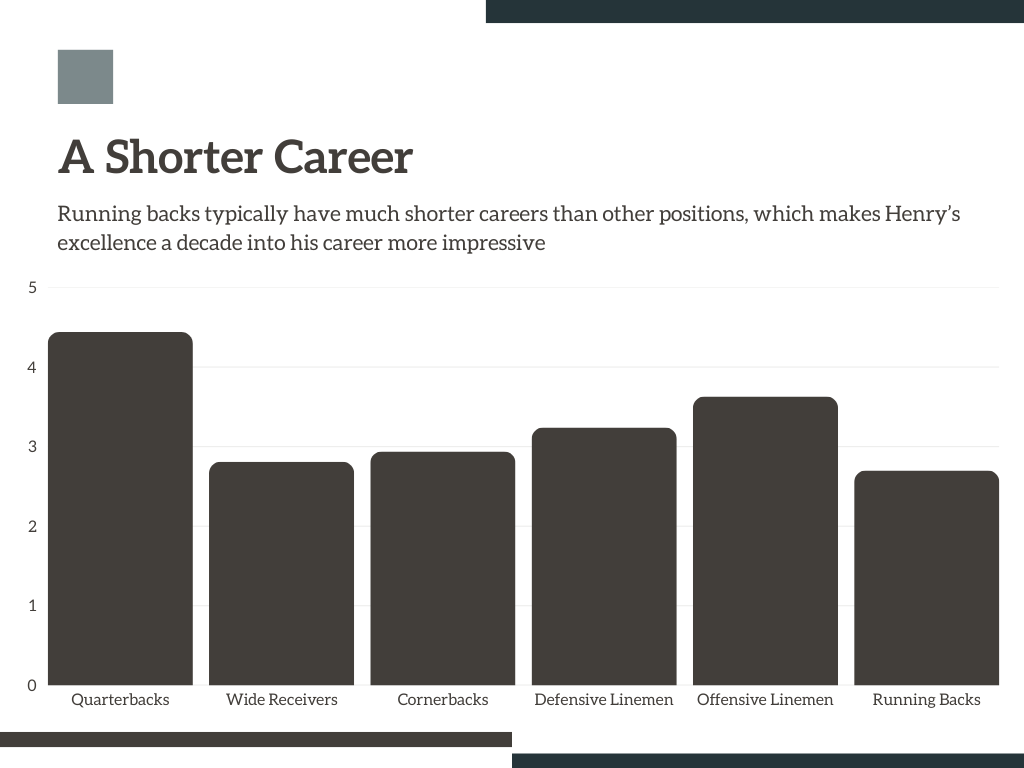

A running back’s career is typically only 2.57 years long and Henry is still running strong in his tenth season. Consider Henry in comparison to someone like Ezekiel Elliot. Elliot was an elite talent at the position and played for nine seasons in Dallas and New England. He led the league in rushing yards twice and received MVP votes as a rookie. After his seventh season he slowed down significantly and was out of the league before he turned 30. Henry, meanwhile, has proven to be a modern phenomenon of the position, continuing to get better as he ages—a true anomaly of the era.

Running Back Specialization

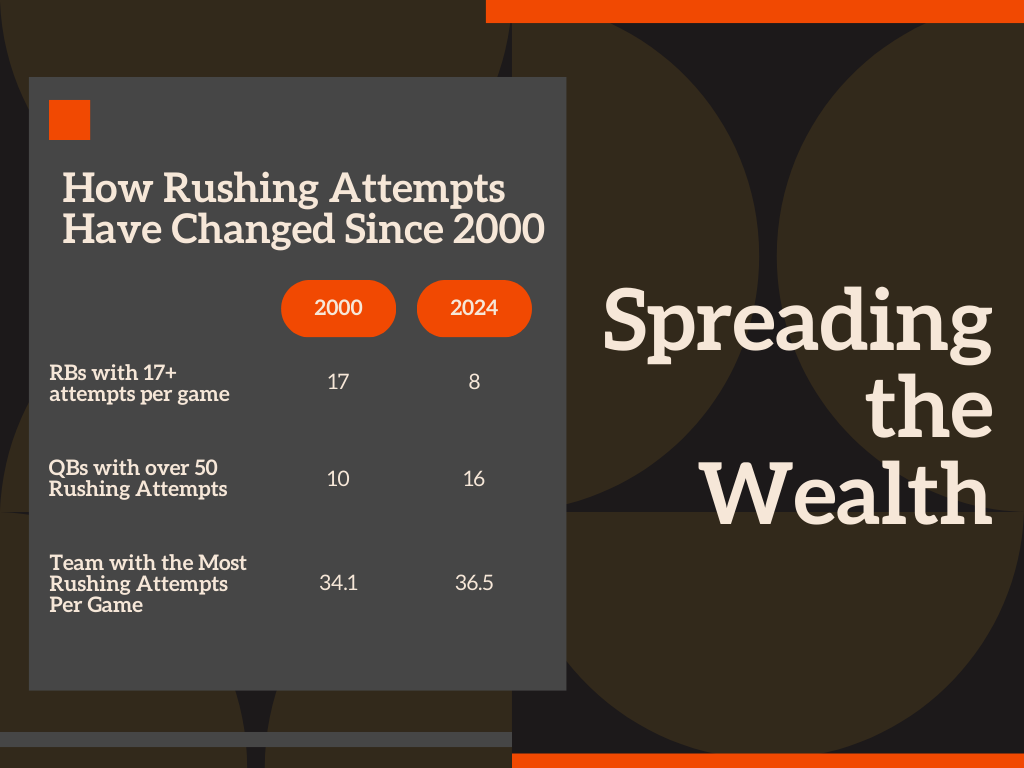

In a bygone era of the NFL, an offense’s most important player was its running back. The way you won games was through a consistent running game and a strong defense. In 2000, eighteen players averaged over 17 rushing attempts per game. Last season, only seven did. The team that ran the most in 2000, the Tennessee Titans, averaged 34.1 rushing attempts per game. This past season, the leading rushing team was the Philadelphia Eagles, who averaged 36.5 rushing attempts per game. The correlation? Teams run it as much as they ever have, but the players that are tasked with the attempts have diversified.

In 2000, Daunte Culpepper led all quarterbacks in rushing attempts with 89 attempts, one of 10 different QBs that accumulated more than 50 carries in that season. In 2024, both Lamar Jackson and Josh Allen registered more than 100 rushes each, and 16 quarterbacks had over 50 rushing attempts. The running quarterback has gone from a niche curiosity to a staple of the best offenses in the league. Those attempts come at the expense of the every-down back.

But even the concept of an every-down back has changed. Derrick Henry and the Eagles’ Saquon Barkley were the exceptions to the rule, with many teams using a platoon system to keep their stable of backs fresh throughout the season. The decrease in touches isn’t the only aspect that has changed, but the way that offenses scheme their running games has as well.

The spread offense concept became popularized in college football before it infiltrated the pro game. This offense utilizes a lot of receivers to create space. These offense have introduced zone-read and run-pass option looks that emphasize timing and creating space. While these misdirection plays are often successful, they are also very scripted. This means that running backs asked to do less improvisation and instead stick to the script. Most coaches are risk averse, so if a play is guaranteed to get three yards as opposed to the chance that it could be improvised to either gain or lose ten yards, they will simply not take the risk.

With the constant rotation of backs in these systems, it becomes difficult for players to establish a flow through repeated carries. Where running backs have been able to show their skills is instead in the passing game through screen passes and swing routes. This has led to an increase in running efficiency in yards per carry, but it has also taken the intrigue out of running the ball.

Consider someone like Reggie Bush. Bush is one of the best running backs to ever play college football. As a junior in 2005, he led the country in yards per attempt with 8.7. This was due in large part to his ability to utilize his speed by bouncing his runs to the outside and making defenders miss. But in the NFL, coaches discourage this behavior because the athletes on defense are so much better than in college, so some of those tendencies were neutered. This creates efficient football, but it doesn’t necessarily create for a memorable player.

The league will continue to prioritize what is analytically sound and safe over the wild unknown of a player trying to dazzle in their own way. And that shift is what makes many running backs feel somewhat uniform. What made Barry Sanders and Walter Payton so great is that the unexpected could be just a second away on any touch. Modern running backs, it seems, are no longer given that luxury.

That is what makes someone like Derrick Henry so unique. He is given the touches, allowing him to develop a rhythm, to utilize his trademark stiff arm, and to flash the mix of power and speed that make him so unique. It’s important for us to appreciate someone like Henry while he is still performing in his prime. Because the institution of professional football has shown us that we may never see an urban legend like him again at the running back position.